One of the truly bewildering traits of human beings is their ability—and even carefree willingness—to ignore facts that conflict with their current worldview. I touched on this topic in an earlier article, and find it manifested in numerous ways in this most viciously anti-rational political climate.

This article looks at data for a timely topic that's a favorite target for fact distortion: Has the U.S. Federal Government workforce grown too large, or not?

The "Tea Party" politicians, in particular, appear to be masters at the art of selling people willful ignorance, perhaps partly because they themselves drink from that cup religiously. Among the false ideas they consider common knowledge is the idea that the Federal workforce needs to be cut—presumably because it, like the Government as a whole, has grown too big. While they're at it, they'd also like to make sure Federal employees don't have a benefits package better than members of their own congregation do.

Recently, a Republican from Texas, Rep. Kevin Brady, submitted a legislative proposal to cut the Federal workforce by 10 percent. According to a Washington Post article, Brady's reasoning goes like this:

There's not a business in America that's survived this recession without right-sizing its workforce, without having to become more productive with fewer workers. The federal government can't be the exception. We're going to have to find a way to serve our constituents and our taxpayers better and quicker and more accurately with fewer workers. I'm convinced we can do it and we don't have a choice.

Including its overall premise, Brady's short statement includes several fallacies, and on Mars we find it alarming to realize that this guy is chairman of the Joint Economic Committee and a senior member of the House Ways and Means Committee. Where I come from, those are pretty big britches! When someone with authority over such enormously important Government functions gets his facts wrong, one has to wonder whether he is deliberately lying for political reasons, or whether he's maliciously failing to determine the facts—instead shaping them to fit his policy goals.

On Mars, such behavior is almost unheard of. When I first revealed it, my fellow Martians had trouble believing that sentient beings could behave this way. And even if someone were to deliberately distort reality, surely Earth's legal systems would be constructed to punish the act.

Apparently, however, this behavior is not only tolerated, it's rewarded by the mere awareness that it's tolerated. After all, if a lie—or deliberate ignorance—by someone in authority isn't challenged, it clearly achieves its purpose. And achieving one's purpose obviously counts as a success. (On Mars, we believe that this is one of the perverse lessons Americans learned from President Richard Nixon's downfall: If you're going to lie, cheat, embezzle, or otherwise commit illegal acts, be sure you aren't caught doing so.)

So, what fallacies does Mr. Brady disseminate in his statement? Here are two obvious ones:

- "There's not a business in America that's survived this recession without right-sizing its workforce." How can this be true? Clearly, as has always been the case, the economic downturn produces not only losers, but winners as well. Yes, the losers will have had to lay off workers, hence the rise in unemployment. But companies in growth sectors will not have done so, and they may even have continued to expand. In this downturn, for example, employment in the oil mining industry increased from 143,000 to 159,000 from 2007 to 2009. A better example is the computer services sector, where employers added 400,000 jobs.

- "The federal government can't be the exception." Someone like Brady who is in charge of National economic policy undoubtedly understands that reducing employment in the Federal sector is never a good thing during a period of slow economic growth. Even economists who aren't sold onKeynesian economics realize that the Federal Government should remain a stable economic player during times like this. Stating otherwise must be a deliberate deception.

That leaves the notion that the U.S. Government must "right-size" its workforce in order to "become more productive with fewer workers." First of all, what does "right-sizing" a workforce mean? If you read Wikipedia's article on the subject, you come away believing that "right-sizing" is merely a euphemism for "layoffs" or "downsizing."

Some dictionaries, on the other hand, suggest there's a nuance to the term that differentiates it from "layoffs." Webster's, for example, defines the term as follows:

To reduce (as a workforce) to an optimal size

"Right-sizing" (or "rightsizing") is a term first uttered on Earth in 1989, when it was really just jargon to justify the downsizing that became de rigeur during the waning years of the first Bush administration. One of the main reasons companies downsize is that their workforce has bulged after a major merger with or acquisition of another company. And as you may recall, starting in the 1980s corporations did a heckuva lot of merging and acquiring. For awhile, even "rollups" where all the rage on Wall Street.

After a merger or major acquisition, it's pretty standard to eliminate inherited workers who do redundant tasks, or those who have a record of poor performance. Companies who downsize for any other reason do so because they're performing poorly, as measured by revenue and profits. In this case, companies downsize to reduce their production costs and make their products or services more competitive.

So, there are two big problems with even suggesting that the Federal Government engage in "right-sizing:"

- Governments are nonprofit institutions, and therefore notions such as competitiveness, profits, and product pricing are meaningless.

- Governments don't merge with or acquire other governments. Well, unless you're talking about conquests, which surely is a special case. Occasionally, governments do split up... for example, when a U.S. State secedes from the Union, or when a country declares its independence from another. In this latter case, of course, the split governments will find the need to "upsize" their workforce rather than downsizing them.

Ah, but what if you believe, as lawmakers such as Brady do, that the cost of the Federal workforce is a major reason why the Federal deficit is ballooning? Well, then I suppose the suggestion does make sense.

As it turns out—and here I'm finally getting to the crux of my argument—the Federal workforce has not been a contributor to the growth in Federal spending. If you're picking up an axe to cut the budget, hacking at the workforce is not only missing the target, but it will actually increase costs in the long run.

As it turns out—and here I'm finally getting to the crux of my argument—the Federal workforce has not been a contributor to the growth in Federal spending. If you're picking up an axe to cut the budget, hacking at the workforce is not only missing the target, but it will actually increase costs in the long run.

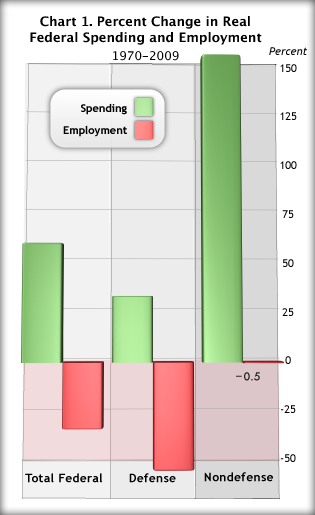

What evidence do I have to support such assertions? Consider the following facts for the 40-year period from 1970 to 2009, as illustrated in the accompanying charts:

- Real (adjusted for inflation) Federal consumption spending increased 56 percent, while total Federal employment fell about 30 percent. Most of the reduction in Federal employment came in the defense sector, but the number of nondefense employees stayed basically flat during this 40-year period while nondefense spending shot up 150% (Chart 1). (Note: The measure of spending shown in chart 1 includes only "current expenditures," which basically counts spending required "to keep the trains running"—that is, to carry out basic agency missions.)

From 1970 to 2009, total Federal employment shrank from 6.1 million to 4.2 million—again, mostly in defense. The nondefense Federal workforce was 1.96 million in 1970, and 1.95 million in 2009 (Chart 2).

From 1970 to 2009, total Federal employment shrank from 6.1 million to 4.2 million—again, mostly in defense. The nondefense Federal workforce was 1.96 million in 1970, and 1.95 million in 2009 (Chart 2). During these 40 years, Federal employment as a percentage of total U.S. employment dropped from 8.6 percent to 3.5 percent (Chart 3).

During these 40 years, Federal employment as a percentage of total U.S. employment dropped from 8.6 percent to 3.5 percent (Chart 3).

These facts make it obvious that the Federal Government has been engaging in "right-sizing" for a very long time. How could Federal employees not be a great deal more efficient and productive today if their numbers haven't changed in the last 40 years, while their workload and output have doubled?

Despite continuous calls for less Federal "intrusion" into taxpayers' lives, taxpayers have simultaneously been demanding and expecting more and more of their National Government. As anyone who has been even marginally observant knows, Federal responsibilities have expanded greatly since 1970. Among its new and expanded assignments are:

- Occupational Safety and Health. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration was created in 1970 to "ensure that employers provide employees with an environment free from recognized hazards, such as exposure to toxic chemicals, excessive noise levels, mechanical dangers, heat or cold stress, or unsanitary conditions."

- Environmental Protection. The Environmental Protection Agency was also created in 1970 and charged with "protecting human health and the environment, by writing and enforcing regulations based on laws passed by Congress."

- National Security. The agencies responsible for ensuring the safety of U.S. citizens have increased employment substantially during this period, especially since the September 11, 2001, attacks by radical Islamic terrorists. The attacks resulted in a reorganization of security functions from various agencies into a new agency, the Office of Homeland Security. The number of Federal security personnel at U.S. airports has also increased, of course.

- Natural Resource Management. In 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, which requires Federal agencies to ensure that their activities "do not jeopardize the existence of any endangered or threatened species of plant or animal or result in the destruction or deterioration of critical habitat of such species."

- National Park System. Numerous Acts and Executive Orders have expanded the responsibilities of the National Park Service since 1970, including the General Authorities Act of 1970, the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978, and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980.

- Drug Abuse. The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 expanded and optimized the Federal Government's ability to control use of illegal drugs. Among other components, the legislation included the Controlled Substances Act, which established drug "schedules," into which various substances would be classified and for which misuse penalties would be defined.

- Many other functions, including Immigration Control (yes, we have been spending more money and hired more people for this), Education, Technology Infrastructure, and Information Dissemination.

Regarding Information Dissemination, consider the huge cost and workload involved in building all the great Federal websites we now have—including the many channels to obtaining customized information from Federal databases never before available.

For example, the charts and data shown in this article come from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the Commerce Department agency responsible for collecting and analyzing statistics on the U.S. economy. BEA is the organization that produces estimates of Gross Domestic Product, personal income, and much more. Their data is now available through an easy-to-use, customizable web interface that generates data in a variety of formats, including tab-delimited, which can be imported into spreadsheet software.

Yes, the Government does much less printing now than it used to, but as one with first-hand knowledge of Federal publishing, let me assure you it costs much more now to publish on the web than printing ever did. For one thing, many agencies were encouraged to—and did—charge fees for printed publications. Obviously, they collect nothing from use of their websites. For another, nearly all Federal printed documents were required by law to use only black ink, or black and one other color. A tiny fraction used the four-color process that's standard for commercial printing.

However, Federal web publishing has been under no such contraints, and so agencies have spent as freely as they thought necessary to make splashy, flashy, and sexy websites that could have been—and often are—designed by a Madison Avenue ad firm. Such sites look nice, but besides being expensive they too often make usability a secondary consideration to appearance. Where once a small agency might spend $500,000 a year on printing, it's now common for it to spend $1 or $2 million on their websites, while still printing some material. (Note: BEA remains a big exception to the norm. Their website eschews expensive graphics and other flashy flourishes, and is mostly easy-to-navigate textual content.)

OK, so it's undeniable that Federal employment has shrunk in the last 40 years, while spending has grown. Doesn't that suggest that Federal employees are much more productive than they were 40 years ago?

Given the data in Chart 1, it's clear that productivity in the Federal sector has risen considerably. However, something must be missing, because it's nearly impossible for an organization to boost output by 50% while cutting its workforce by 30%. In fact, if you lay these data beside analogous ones for the private sector,  it appears that the Feds have been using some secret productivity weapon that they should now share with the private sector, so that it can downsize as the Feds have done. (Oops... no, that would cause a huge recession, actually.)

it appears that the Feds have been using some secret productivity weapon that they should now share with the private sector, so that it can downsize as the Feds have done. (Oops... no, that would cause a huge recession, actually.)

Since 1970, output of private industry has shot up 200%, but this was accompanied by a 70% increase in employment (Chart 4). This means that the gain in private output required 70 percent more workers over this period. If you apply that relationship to the public sector, Federal employment should have increased 15-20 percent to support its 50% growth in output over these 40 years.

So how did they do it? How could the Federal sector manage to increase output by 50% while actually reducing employment? The truth is, they couldn't have done, despite what the data show. For even though the data are correct for what they do measure, they are missing a big component of the puzzle, as you'll see.

The Missing Employment Data

Since Jimmy Carter came to office in 1976, every President except for George H.W. Bush has called for either cuts in or freezes on Federal hiring. This explains why Federal employment has remained flat for 40 years... it has been continuously downsized.1

Given this history, today's calls for cuts in Federal employment are either dishonest and politically motivated, or they are misguided and made by ignorant politicians who have no business being in charge of the Nation's business.

The ugly truth is that for every Federal worker who hasn't been hired since 1970, one or two private-sector employees has been. For most of these 40 years, both the Executive and Legislative branches of the U.S. Government, whether led by Republicans or Democrats, have bought into the notion that "contracting out" (or "outsourcing") Federal jobs was a good way of stretching precious Federal dollars.

But this is simply not the case, for two simple reasons, which I plan to take up in a future article on Federal contracting:

- Inefficiency. Outsourcing to private companies is often much more expensive than retaining work inhouse. Briefly, this is the result of:

- Additional Overhead. Most large contracts are subcontracted, and even subcontracts are subcontracted. Each layer adds to the overhead cost of every dollar spent.

- Inflexibility. Getting rid of bad Federal contractors can be as difficult as getting rid of a bad Federal employee.

- Incompetence or dishonesty. Scrutiny of the background and expertise of companies hired by the government is much less exacting than that of potential employees. Too often, companies overstate their qualifications for a particular type of work, overstate costs, or both. Even when the private enterprise is at fault, the government agency loses time as work must be redone, and typically must shell out additional funds for the privilege.

- Lack of continuity. When a company is newly hired to assume an existing task, it's far too easy for them to claim that the outgoing contractor had been "doing things wrong." Without continuity, Federal managers can face unmeasured duplication of costs merely because the new contractor has a different way of doing things. Sometimes a change is warranted, but too often it is not. This kind of waste can also occur when Federal managers change, but that happens far less frequently.

- Conflict of interest. Private contractors are motivated by profit rather than by public service, and therefore should never be in charge of making policy or spending decisions that affect taxpayers. This is a clear conflict of interest situation, where the private company's goal is to make as much money as possible, and the Government's goal is to serve the public as best it can within its limited means.

Even if you don't see it the way we do on Mars, you will surely find it strange—and disturbing—that the Federal Government has absolutely no idea how many employees it has in the private sector.

If you walk through any Federal office today, you won't be able to tell which employees are contractors and which are on the Federal payroll. For all appearances, everyone there is a Federal employee. Yet they're not, and nobody keeps tabs on the ones who aren't, except to make sure they have the appropriate network accounts, desks, computers, and security badges. The Labor Department, which is responsible for collecting the Nation's employment data, has never included this information as part of its surveys.

Among other management consequences of this irresponsible lack of data is that it's impossible to know whether the Federal workforce is "right-sized" or not. It's also impossible to measure relative employment costs, or to compare productivity for the two groups.

And why do we not have these necessary data on private contractors?

First, the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980—one of a series of misguided deregulation moves in the 1980s designed to get the Federal Government "off the backs" of private companies—made it extremely difficult for Federal agencies to add new questions to their existing surveys. And second, the lack of knowledge has been a mutually beneficial "wink" among cash-strapped Federal managers, cash-hungry private companies, and dishonest/ignorant legislators who want to claim they're cutting costs by keeping a lid on Federal employment.

Only in the last few years has the superiority of outsourcing public jobs been openly questioned, and that's been spurred mainly by concerns about the propriety and cost of contracting by the State and Defense Departments to support the War in Iraq. Yet all through the George W. Bush years, Federal agencies were under extreme pressure to "privatize" or "contract-out" any functions that weren't "inherently governmental in nature."

Now, I know what "privatizing" means, ugly word though it may be. But no one—including those pushing hardest for it—can explain what an "inherently governmental" function is. If they were honest, such advocates would admit that any public function that becomes the object of lust by some industry group's lobbyists could not possibly be "inherently governmental," and therefore could be a candidate for privatizing or outsourcing.

To hear these people talk, the only "inherently governmental" jobs are those that make and administer budgets and contracts. That means no jobs for

- Clerks

- Scientists

- Engineers

- Computer specialists

- Designers

- Webmasters

- Economists

- Statisticians

- Audio/Video specialists

- Public affairs specialists

- Writers

- Editors

- Security specialists

- Meeting planners

- Travel planners

- Programmers

- Systems designers

- Accountants

- Budget analysts

- Etc.

This leaves jobs only for

- Lawyers

- Administrators

- Managers

- Budget officers

- Contracting officers

- Personnel officers

Myth of the Coddled Federal Worker

One final piece of the puzzle behind the recent calls for Federal downsizing, workforce attrition, and worker pay caps is the myth that Federal workers cost more than their private-sector counterparts, because of their great benefits. Legislators like Brady love to stick this one in their speeches because it's a guaranteed applause line, especially during great recessions.

Trouble is, it's not true.

I'm going to sidestep the whole debate about whether Federal salaries or higher or lower than comparable jobs in the private sector, because it's too complicated for a few paragraphs and perhaps even for an entire book. There are numerous problems with this analysis, including the difficulty of finding consistent data that tracks all the relevant variables —including worker age, education, experience, location, and job descriptions.

Under President George H.W. Bush, Congress passed legislation that granted Federal workers additional pay under a system of "locality adjustments." President Clinton more or less moth-balled the system, and then set one up that was a pale shadow of the original. Here's a link for more information on the topic.

Since the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) was mothballed in 1986, all new Federal workers have been in the Federal Employee Retirement System (FERS). FERS does offer a small pension, but it's nothing like the one CSRS retirees enjoy. In addition, FERS workers pay a much higher portion of their salaries for that pension than CSRS workers did.

Instead, a FERS retirement is heavily dependent on the Federal Thrift Plan, which is nothing more than a 401K program for Federal employees. (Federal workers don't have 401K plans.)

Federal employees have health care, sick leave, vacation leave, and other benefits that are comparable to those in any large U.S. company. I'll never forget moving from a Federal job at BEA to Citibank back in 1996, and finding that Citibank's benefits were superior to those I'd had in the government. Not only that, my pay was almost double, and I didn't have any onerous supervisory responsibilities. Citibank's pension system wasn't as generous as that from CSRS, but it was comparable to that of FERS.

Are Federal benefits better than those of your typical small company? Yes, very likely they are. And, given the vast difference between a Federal agency of 100,000 and your typical small company of 50, the difference is appropriate.

In any case, very few Federal contracts are awarded to your typical small company. At least, not directly. Any small companies that share in contract spending get work only through some "prime" contractor, not directly by some Federal manager.

CSRS was abolished not only to reduce the pay of Federal retirees, but also to add the Federal workforce to the Social Security pool. Under CSRS, Feds neither paid Social Security nor received its benefits on retirement. Under FERS, they do both in the same way that private sector workers do.

Another reason why Federal employees still have a decent package of benefits is that they are represented by a Labor Union, the National Federation of Federal Employees. If workers in U.S. companies get desperate enough, perhaps they'll recall that having a Union on your side is a good thing in the fight for decent pay and benefits. That's a lesson that's been lost over the years, especially since President Reagan started kicking Unions in the butt back in 1982.

However, just because workers don't have the pay, benefits, and pension they should have doesn't make it OK for them to demand cuts for those who do.

And politicians like Mr. Brady should know better.